A Reflection on Beth Chatto’s Meanwhile Garden: The Urban Wild and Other Disturbances

A sold out evening with the Cultural Engine Research Group’s Imaginarium, on 12th February 2026 at the Commons Café, The Minories, Colchester, Essex.

The evening opened with Stuart Bowditch’s performance of “Homage to the Waiting Room.”

Given Colchester’s history of former “meanwhile” spaces, Stuart’s previous fieldwork on the site of the Waiting Room makers/hackers space (above) helped to subtly and audibly evoke the evening’s theme of disturbance.

Giles Tofield (below) from the Cultural Engine Research Group introduced the audience to the evening as a central part of the experimental approach of CERG, taking disruptive “pop up” critical theory into pubs and other community spaces in order to challenge the notion that knowledge belongs behind a university paywall. CERG started in 2014 with Club Critical Theory (including a performance by Stuart Bowditch) after the introduction of 9k tutional fees and the rise of Brexit. In the current crisis of the failing neoliberal education business model, this outreach project feels less like an experiment and more like an imperative.

We need a new Faculty of the Imagination.

Giles introduced the second Imaginarium (see reflections on the first) as moving through layers of disturbance: from policy frameworks, like the Local Nature Recovery Strategy introduced by Elias Watson from Essex County Council (below), through cultural, scientific, and finally into radical horticultural practices of ecological disturbance.

Part One: Cultural Disturbance or How to Capture the Sounds of Capitalism

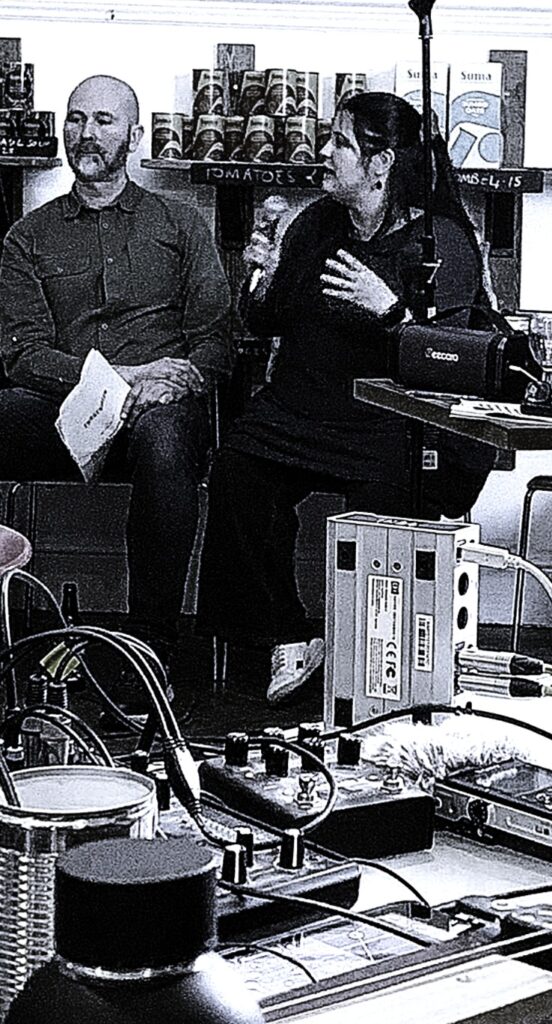

Tony Sampson (above) approached the core ambition of this rendition of the Imaginarium project: to explore “avant gardening” – a term first credited to a 1970s punk band – as a way of approaching the disconnect between the environment and ordinary life. The Imaginarium recognises that the former is not a distant concept but something immediate and ordinarily related to the latter. While acknowledging the importnace of art and culture, as well as the work of philosophers like A.N. Whitehead who looked to undo the tradition of bifurcating culture and nature, the Imaginarium needs to address the difficulty of engaging people with nature when they are “too busy struggling to stay in work and pay their bills.”

The artists in this first session focused on how disturbance functions within their individual practices. This specifically engaged with cultural practices that engaged with overlooked noises, neglected ambience, interruption, friction, and glitch. The session was interested in exploring the points at which these elements enter the artist’s work and how they operate as creative tools rather than mere accidents.

We began with two of Elena Botts’ (second from left above) experimental films titled “some little works” and Elena’s poetry reading which expressed a glitched sensibility for disturbance. In the discussion, Elena spoke about how journeying between the disturbances of “natural” and “urban” settings inform her work. The experience served as a perfect entry point to explore how interplays between sonic, social, and ecological disruptions shape a “journey” or process in art.

Stuart Bowditch (third on the left above) addressed the challenge of sustaining disturbance without neutralising it, how art can “stay with” disruption and how artists might keep disturbance active in their work. Disturbance can be thought of as an avoidance of overproduction or the rendering of art as safe and anesthetised.

Matt Shenton (fourth on the left above) ventured into the political potential of disturbed performance, pointedly describing his practice in terms of recording the “Sounds of Capitalism.” This proved to be a highly influential term on the evening, provoking questions about how tension between environment and politics might become more audible through cultural practices, and whether the work helps formulate questions that would otherwise remain unheard, ignored, or managed away by dominant political discourses ebbing ever-increasingly toward all out denial.

Matt’s wonderfully adventurous and experimental performance of an “Invitation to Disrupt” subsequently offered an approach to sound as interruption, as provocation, as possibility.

Overall, the first panel helped to [re]frame disturbance as a space of cultural and political possibility rather than a mere crisis to be managed or denied. The performances invited reflection on how the cultural performance of disturbance might expand collective attention, draw attention to shared vulnerability, explore environmental care, and ultimately contribute to new forms of cultural and political imagination.

Interlude: The Science of Disturbance

After the break (and the amazing food at the Commons!), the evening shifted registers from the aesthetic to the scientific. Whereas the artists offered us ways of sensing disturbance in cultural expression, the scientists introduced tangible, nature-based approaches, including habitat creation, and the tensions between newly made and long protected reserves.

Nonetheless, despite differences in artist and scientific experimentation, these presentations suggested a comparable notion of disturbance in nature as not simply about destruction but process, and something that clears space for potential resilience.

Kristina Chilver (above) explained that marine ecosystems are fundamentally shaped by movement and disturbance rather than stillness. Events such as storms, sediment shifts, ice scour, and heatwaves actively disrupt the existing structure, alongside biological activities like grazing and burrowing. These disturbances remove dominant organisms, expose new surfaces, and free up nutrients and light, which prevents any single species from dominating indefinitely. In this sense, what may appear to be damage is often a natural process of ecological renewal and reconnection.

Dhruti Bell (above) contended that humans are intrinsically linked to these disturbance patterns, but modern human activity now operates at a scale that can override natural ecological limits. The creation of human-made habitats and the introduction of unchecked disturbance can push ecosystems beyond their ability to recover. Even within nature reserves, where protection is intended to preserve ecosystems, the absence of natural disturbance can sometimes lead to imbalances, just as excessive human induced disturbance can cause degradation elsewhere.

While disturbance is a natural and necessary force in marine environments and other habitats, ensuring that winners do not win forever, human influence risks turning beneficial disruption into lasting damage when ecological limits are exceeded.

This session provoked questions concerning how the impulse to protect nature might sometimes be as problematic as our impulse to exploit it. Are we learning to manage, and what is the right balance between protection and learning to let it be?

Part Two: Ecological Practices in Disturbance

The second session brought us back to the garden, specifically to the Meanwhile Garden itself, growing on the rubble of Colchester’s old bus station and the former “Waiting Room” hacker space.

The Meanwhile Gardener David Gates (above) introduced the story of a place grown on a postindustrial brownfield site, where the messiness of urban neglect and Beth Chatto’s philosophy of “right plant, right place” meet. The garden is not imposed on this space. It is co-curated by artists, by experimental gardeners, and most compellingly, by nature itself. It stands as proof that disturbance, when tended with care rather than control, can transform dereliction into connection. What brings culture and nature together is not resolution but the willingness to stay with the trouble, to let disturbance teach us how to grow with it.

Darryl Moore (above) framed his discussion on the Meanwhile Garden by drawing a powerful parallel between ecological and social disturbance. He opened with the concept that ecosystems are shaped by disruption rather than stasis, then linked this to a critique of capitalism, quoting its tendency toward the “uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions.” This set up a central tension that echoed throughout the evening: is disturbance a progressive force for change, or does it become destructive when unchecked by ethical limits? He positioned disruptive technology, resistance, and “ecological metabolisms” as key factors in navigating this balance, questioning whether constant upheaval serves life or simply serves the system.

John Little (above) offered an animated practical case study in this tension, particularly around the concept of “edgelands” and bringing in postindustrial sites like Canvey Wick that are rich in biodiversity yet often dismissed as derelict. He raised a significant question that hovered at the edges of the evening’s discussion: “When does dereliction become neglect?” Noting that neglect can be “good for biodiversity but bad for people,” he explored how disrupted places often become wildlife havens while remaining unwelcoming or inaccessible to communities. Contrasting this with gardens and allotments as spaces “disrupted by people’s taste and optimism,” he ultimately positioned gardeners as the “urban cornerstone” capable of transforming neglect into joy. His conclusion was a call to action that felt both urgent and achievable: to move public investment “from capital into care,” recognising that thoughtful, careful disruption by skilled gardeners can rebuild both ecological health and human connection.

What’s Next?

Stuart Bowditch and Matt Shenton performed together for the closing drinks, ending a packed evening that had moved through policy, art, science, and horticultural practice via different modes of experimentation. It was an evening in which ecologists, gardeners, and sound artists invited us to listen differently, to perceive differently, and to imagine what disturbance might mean, differently.

As the artist Lora Azis reminded us, at the first Imaginarium in Sept 2025, nature needs to be welcomed inside our cultural spaces. Meanwhile, just a few yards outside the venue, in the raw chill of this dark, damp February evening, the Garden was there. It is not a metaphor! It is, in this meanwhile space, a living experiential reminder that the questions raised tonight are not simply abstract.

To conclude, then, to better grasp the urban wild, and these other disturbances, we need to perhaps look more closely in the rubble where neglect persists, and yet things tend to grow. The ambition is not to sideline or eliminate disturbance. It is learn how to live and work with it, to stay with it culturally, critically, and politically; to let it inform a struggle in a much broader ecological space of possibility than we can ever possibly imagine (or win) alone. That is to say, we need to explore how to expand these spaces to open up new forms of collective imagination that connect environmental care and creativity.

The Imaginarium will return…

Tony Sampson (CERG) 18/02/2026

The original context and programme for this event can be found here: https://culturalengine.org.uk/imaginarium-returns/

Speaker and Performer Bios

Cultural Engine Research Group (CERG) https://culturalengine.org.uk/news-blog/

The first CERG Imaginarium took place on 27th September 2025. For more information visit: https://culturalengine.org.uk/ongoing-coverage-of-the-first-wild-essex-imaginarium-27th-sept-2025-ebs-uoe/

Elias Watson is the fulltime Local Nature Recovery Coordinator for Essex County Council.

Stuart Bowditch’s practice is located in places and communities that exist on the fringes, both geographically and socially, with a particular interest in the sonic landscape, capturing overlooked and overheard noises and using sound as a documentative and creative medium. https://www.stuartbowditch.co.uk/

Dhruti Bell has been working in the conservation and environmental engineering sectors, managing habitats as an RSPB warden and working on ecology, habitat creation, community engagement, and planning applications. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Essex researching the socioecological impacts of newly created versus long term protected nature reserves.

Elena Botts is an artist and postgrad researcher at Essex who organises a project loosely termed “unknown sound collective” intended as an archive of experimental artists’ interior worlds, these that are externalised through their work, and the interchange through artist communities around the world, and the social change this may or may not represent.

Kristina Chilver is a PhD Researcher in Coastal Nature based Solutions, a Marine Biology graduate, and conservation ecologist from Colchester, Essex. With a background in ecological consultancy and coastal field research, her work focuses on nature based solutions for ecosystem restoration and climate resilience. She is passionate about integrating science, policy, and community perspectives to protect coastal environments.

Matt Shenton is an experimental musician, sound artist and performer. He uses manipulated field recordings, scavenged objects and homemade instruments to explore absence in modern rural soundscapes. www.matthewshenton.co.uk

David Gates is the Meanwhile Gardener for the renowned Beth Chatto’s Plants and Gardens in Colchester, a project inspired by the legendary plantswoman Beth Chatto, known for her philosophy of “right plant, right place.” Gates leads the development of the “Meanwhile Garden” on a brownfield site, focusing on ecological design and community engagement, applying Chatto’s principles to create resilient, wildlife friendly spaces from challenging urban environments.

John Little has been reimagining what urban nature can be since founding the Grass Roof Company in 1998. Over the past 25 plus years, John has designed and built more than 400 small green roof structures and various other species rich planting with walls engineered for nesting, hibernation, and year round habitat. John argues: “Put the best gardeners in the poorest places”; “Move money from capital into care”; “Understand that gardened places are best for biodiversity and people”. Instagram @grassroofco

Darryl Moore FRSA is an award-winning garden and landscape designer. His diverse skillset and wide-ranging knowledge base are formed from studies in Art History, Philosophy, Mechanical, Sound Design, and Garden Design. Darryl is also an award-winning garden writer and photographer.

Special thanks to everyone at the Commons Cafe, including Jo, Marley et al, and to the Cultural Engines’ Sean Mcloughlin for vital support and images of the night.

Leave a Comment